FPP/CMS Chicago 2026 Speaker Exclusive: The banker’s reality check, and why it matters in Chicago

After a decade of hype, capital has sobered up. Investment banker Adam Bergman explains why alternative proteins are colliding with venture reality, where money is still willing to flow, and what founders must unlearn to survive the next phase of scale

For much of the past decade, alternative proteins marketed themselves like software: scale fast, capture a market, ring the bell. Then reality arrived, on grocery shelves and in fundraising data rooms, with the friction of biology, manufacturing, and consumer habit.

Adam Bergman, Managing Director at EcoTech Capital, has been watching that collision up close. An investment banker and advisor for three decades, he worked with companies “to help them go from where they are today to achieve an exit”, and he has grown increasingly blunt about what capital is willing to fund, and what it is no longer willing to pretend is true.

At The Future of Protein Production Chicago, co-located with the Cultured Meat Symposium, Bergman is slated to bring that bluntness to the stage across two sessions: a fireside chat titled Financial Lessons From The Front alongside Sean Lacoursiere (Maia Farms), Tony Martens (Plantible Food), and Niya Gupta (Fork & Good), plus a panel titled Navigating Investor Skepticism & Leveraging Opportunities in a Rapidly Evolving Market.

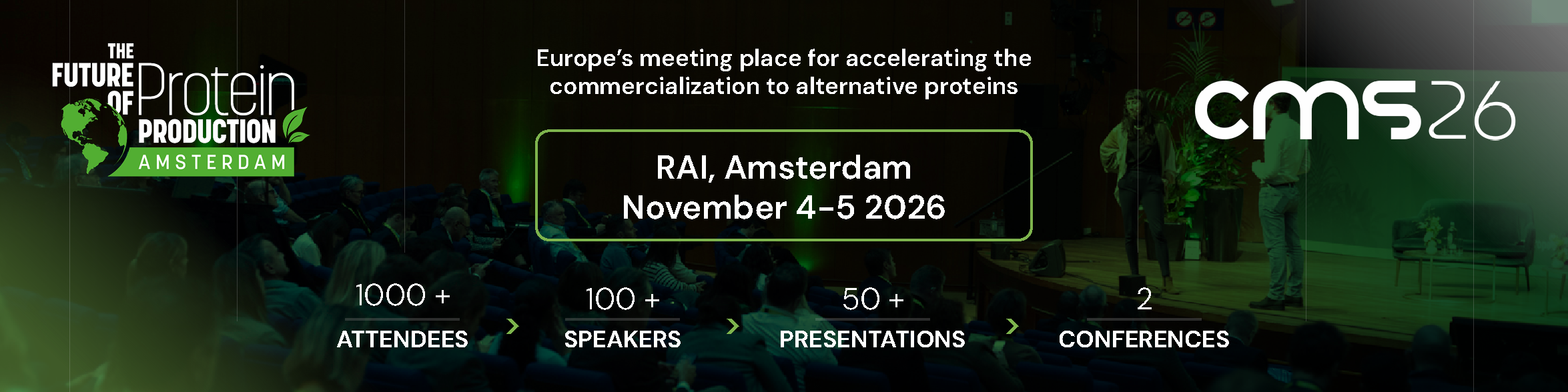

The event takes place February 24-25, 2026, at McCormick Place in Chicago, with one ticket granting access to both conference programs.

The venture clock versus the fermentation calendar

Bergman’s argument starts with time. Venture capital, he noted, tends to run on a five to seven-year horizon. “We’re typically talking it’s going to take a decade [to achieve an exit],” he said in a recent Future of Foods podcast interview with Alex Crisp. The mismatch is not philosophical, it is structural, and it bleeds into everything: valuation, hiring, factory timelines, and what founders feel forced to promise.

That mismatch also helps explain why so many decks from the boom years now read like artifacts from a different macroeconomy. In 2020 and 2021, he recalled, “there were hundreds of investors looking at the Food Tech sector”, buoyed by a media cycle that made plant-based seem inevitable. The future, briefly, looked like a set of brand activations. Burger King commercials. Dunkin’ menu items. A narrative so loud it could drown out execution risk.

Then, as Bergman put it, “people started realizing that this trend was maybe oversold”.

The painful twist is that many companies did not fail because their products were terrible. “A lot of it is the market just never developed to the level people thought it was going to.”

A smaller pool, a harder story

One of Bergman’s recurring themes is that capital did not vanish. It moved. Some investors ran out of dry powder. Some saved what remained for triage inside their portfolios. Some simply stopped wanting to explain to their own backers why exits were still theoretical.

“A lot of these investors have just left the market,” he said. “They kind of said, ‘Okay, we were wrong’.”

That leaves founders trying to finance new technology with a narrower set of checks, and a much stricter audience. The pitch, Bergman argued, is now less about vibes and more about forensic credibility. “We need to really craft a story,” he said, including “explain why we didn’t achieve what we said we were going to”, and “what the realistic time horizon is.”

In that environment, he framed his role more as a translator between scientific ambition and capital-market skepticism. “When times are difficult like they are today, this is when investment bankers show their value,” he said, “because they can be real connectors with capital and companies.”

We turn down working with probably 75% of the companies who approach us

But he is also selective. “We turn down working with probably 75% of the companies who approach us,” he said. He looks for three things: what is genuinely exciting about the company, whether its model matches both history and reality, and what risks could break the business even if the science works. “You could have the greatest opportunity. You could have a fantastic product,” he said. “If you have three or four major risk factors… it’s very clear quickly to me what’s viable and what’s not.”

Where the market actually is, not where it was supposed to be

The early promise of alternative proteins leaned on an implicit assumption: that demand would compound quickly once consumers tasted 'the future'. Bergman described a different trajectory. Plant-based, in his telling, ran into the blunt physics of taste, texture, cost. “Beyond Meat and Impossible had a nice initial growth, but have plateaued or gone down,” he said. “The sector hasn’t continued growing.”

That matters because it reframes what 'success' looks like. If the market is not sprinting toward 20% share, the right strategies start to look less like disruption and more like supply chain patching: ingredients, blending, and products that fit into existing consumption patterns.

Bergman repeatedly returned to what he called “the gap between protein supply and protein demand”, and the idea that future proteins’ near-term job is to fill it. “There is a gap today that is getting larger every year,” he said, pointing to tightening animal supply and higher prices.

The near-term “most promising” territory, in his view, sits in “precision biomass fermentation”, especially as “an ingredient play for B2B”, plus a pragmatic resurgence of blends. “I think blending is a good opportunity to take a finite amount of meat and help extend it,” he said, adding, “I think you’re going to see a lot more blending.”

If you can build these products to get the taste and texture right and mouthfeel, I think all of it’s fine. The problem’s been a lot of these products have not been up to the same level in taste, texture, or cost

He described the logic with a fast-food anecdote that cuts through purity narratives. “If you buy a Whopper, you’re probably not buying it because you’re really excited to taste the taste of the meat,” he said. In other words: if the product experience is right, and the price is right, many consumers will not interrogate the ingredient list the way activists do. “If you can build these products to get the taste and texture right and mouthfeel, I think all of it’s fine,” he said. “The problem’s been a lot of these products have not been up to the same level in taste, texture, or cost.”

Cultivated meat’s integration problem

On cultivated meat, Bergman sounded neither dismissive nor romantic. He compared it to biotech in the 1990s: early, expensive, and slow to scale. “Cultivated meat is going to go through the same process,” he said.

But he drew a sharp distinction between biotech’s pricing power and meat’s. “Those drugs… have the opportunity to sell for thousands,” he said. “The challenge that the cultivated sector has is it has to sell meat.” And that means you cannot “try to sell it at 10 times what your current beef price is.”

He also questioned the sector’s tendency to vertically integrate everything at once. “They are trying to do everything,” he said of cultivated startups: cells, media, bioreactors, scale-up, production. “I don’t think that’s how the meat industry works.” Over time, he argued, specialization is more likely to drive costs down. “If everyone tries to be a jack of all trades, it’s both difficult and expensive.”

That skepticism about integration aligns closely with the theme of his Chicago panel, which explicitly frames investor caution around “delayed timelines to commercial scale” and “high capital costs for manufacturing infrastructure”, while pointing to nearer-term opportunity in “precision fermentation, biomass fermentation, and high-value ingredients like cultivated fat”.

Government as customer, not referee

When public money enters the discussion, Bergman’s instincts are shaped by an earlier career chapter in cleantech. Grants can help, he said, but they are not the core solution. He worries about governments attempting to pick winners in technologies that are still failing at a high rate. “It’s really difficult for governments,” he said, noting that even venture investors misjudge outcomes with depressing regularity.

His preferred model is procurement. “I actually think the role is much less funding and much more being a customer,” he said, pointing to schools and the military as potential anchor demand. “Could they be the initial customer that drives upscale so these companies can get their cost structures down?”

The political context matters, too. Food is tribal, cultural, and easily weaponized. “If this is what your family does and someone says, ‘Oh, you can’t do that anymore’, you’re attacking my culture and traditions,” he said. The consequence is that innovation in protein is never just technical. It is narrative, identity, and power.

What he will push founders to admit, onstage

If Bergman has one consistent warning, it is about valuation as self-inflicted gravity. “Companies raised a tremendous amount of capital, much more money than they needed,” he said, “and they did it at very high valuations”. That sets expectations for “+20%” annual returns and pressures companies into “financial plans that were just unachievable”, not because the business is bad, but because the timeline is.

His positive case, by contrast, is almost boring, and that is the point. He looked for “a viable product that has a differentiation”, defensible IP, and founders with “a vision, but also… reality”.

Believer Meats is not the last cultivated meat company to go bankrupt. We’re going to see a lot of other bankruptcies in this industry

He also looked past the current slump. “I’m a bit bearish on today,” he said, “but if you fast forward… I think you’re going to see the product mix of protein change dramatically over the next two decades.” The industry, he warned, will get there through attrition as much as through breakthroughs. “Believer Meats is not the last cultivated meat company to go bankrupt,” he said. “We’re going to see a lot of other bankruptcies in this industry.”

But the payoff, he argued, is path-dependent. A single breakout success can reshape the risk appetite of everyone watching. “We need some sort of a Food Tech Tesla,” he said, “because if we do that, you’ll see a lot more money come in.”

In Chicago, he is unlikely to offer comfort. The value of his presence is that he does not need to. He is coming to talk about capital the way capital talks privately: about timelines, exits, and the cost of pretending biology behaves like software.

More than 100 speakers will be taking to the stage at The Future of Protein Production/Cultured Meat Symposium on 24/25 February 2026. To join them and more than 400 other attendees, book your conference ticket today and use the code, 'PPTI10', for an extra 10% discount on the current rate. Click here. If you just want to walk the exhibition floor, meet the experts and network with the delegates, book your free pass here

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)

.webp)