Will customers accept less meat in their cafeteria meals?

Meat consumption in industrial nations is much too high and this not only increases the risk of e.g. cardiovascular diseases. Increasing levels of animal husbandry also aggravate the global food problem because the cultivation of animal feed uses valuable land that could be used to produce human food.

Animal husbandry also contributes to climate change. Ruminants produce the greenhouse gas methane, while much more energy is consumed when producing food of animal origin than for plant-based alternatives. "Meat is more expensive than most of the side dishes," said Junior Professor Dr Dominic Lemken from the Institute for Food and Resource Economics (ILR) at the University of Bonn. "Cafeterias want to reduce the meat portions on their plates for cost reasons alone."

What happens with customers who are accustomed to eating meat? The question is what incentives are needed to encourage customers who are accustomed to consuming animal products to accept less meat and more sides or accompaniments on their plates. A team headed by Dominic Lemken supported by Gloria Sindermann at the University of Göttingen carried out a study in a cafeteria at a rehabilitation clinic that serves around 200 portions of food every day to find out the answer. The paper is published in the journal Environment and Behavior.

The researchers logged data on a total of 5,966 meals chosen by customers from October 2022 until May 2023 – including information on whether the plates contained meat and what portions of meat were served. The study was carried out anonymously and unnoticed by customers. The researchers also asked 125 customers whether they were satisfied with their meal.

The researchers had agreed a plan with the owners of the cafeteria before the study began. No changes were made during an initial six-week observation phase and the staff at the cafeteria only amended the meat portions if this was specifically requested by customers. The staff then changed their approach at the counter during a second more active phase by asking: How much meat do you want?

An information board also informed customers that taking smaller portions of meat would help to feed more people around the world. In a third phase, customers were automatically given less meat on their plates. Signs on the serving counter informed customers that they could also ask for a bigger portion if they wished. However, the staff only served a bigger portion if requested by the customer.

The strategy used in the final phase is a type of 'default nudging', in which a nudge is used to trigger a desired change in behavior in a targeted way. The shocking images on cigarette packs designed to discourage smokers are a good example of a nudge. "In contrast, the nudge in our study was that smaller portions of meat were served by default and customers had to make more effort to ask for a larger portion," said doctoral candidate Ana Ines Estevez Magnasco from the team at the ILR. Customers found it more comfortable to simply accept a smaller portion of meat.

During the study, a total of eleven different meals such as spaghetti bolognese, lamb curry or chicken fricassee were served with a third less meat on average and with more of their normal sides or accompaniments. The completed questionnaires showed that this was largely welcomed by customers. However, the various strategies had significantly different effects when it came to reducing meat portions.

At the beginning of the study – when everything remained as normal – only about 10% of customers asked for a smaller portion of meat. In response to the active question "How much meat do you want?," the proportion of people ordering a smaller portion increased to almost 39%. Yet this figure soared to more than 90% with the nudge – i.e. only serving more meat when requested by the customer.

"A noteworthy aspect was the fact that women and men behaved very differently," added Dr Aline Simonetti from Lemken's team. This was especially noticeable when customers were asked "How much meat do you want?" – with almost four times as many women asking for a smaller portion than was the case with men. There was still a difference with the nudge – serving a smaller portion of meat by default – although it was less pronounced.

"We observed that nudging evened out the decisions made by men and women about whether to accept a smaller portion of meat," summarized Lemken.

"This result could also be used in public food policy when it comes to overall meat consumption," according to the researcher, who is also a member of the transdisciplinary research areas 'Individuals & Societies' and 'Sustainable Futures' at the University of Bonn.

How can cafeterias use these findings? Lemken recommends that cafeterias initially carry out surveys to find out whether smaller portions would be accepted as standard. "If customers reject this idea, the staff could actively ask customers how much meat they want when serving the food so as not to alienate anybody," says the economist. However, there is still a need for more research in this area because there are sometimes significant differences between the range of food served by cafeterias and their regular clientele.

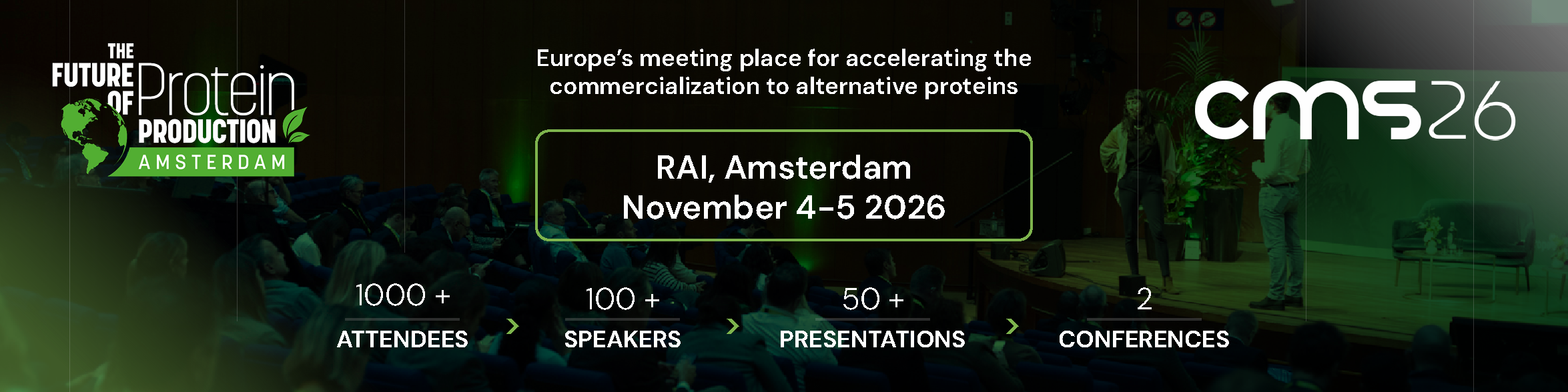

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)