Unique manufacturing method produces more appealing vegan meat

Food technology researchers at Lund University in Sweden have developed a way to make vegan food more appetizing by using new combinations of raw materials. So far, the research field for plant-based meat imitations, known as meat analogs, has been very small – but is set to explode. The team at Lund is among those that have published the most research in the world on the topic.

The research is similar to that surrounding cultivated meat. However, instead of cultivating meat by using stem cells, researchers work with with plant protein as a means to imitate the fundamentally different muscle fibers.

An evaluation of several crispy 'meaty' plant-based products was recently carried out. Some were rated highly, but one stood out as the winner. Texture and temperature are just as important as taste for how food is sensed in the mouth.

"This is generally referred to as the three Ts: texture, temperature and taste," said Jeanette Purhagen. "Texture, or consistency, affects how much we like the food, just as much as taste, although we are not always aware of it. Both have to work."

Purhagen is a researcher in food technology at Lund University and develops new ways to make appetizing food from different types of residual streams generated by the food industry – with benefits for the environment, climate, health and animals. Food texture is her area of specialist expertise.

The vegan food currently in supermarkets – often containing imported soy protein as the main ingredient, or other types of bean and vegetable burgers – lacks the fiber structure required to provide the chewiness that people appreciate.

"If, for example, you take mashed potato and fry it, your teeth go straight through, it is just soft and fluffy. When you chew meat, it is a totally different sensation," added Purhagen's colleague, Karolina Östbring. "With the help of technology, we want to introduce chewiness into vegetable-based foods by imitating muscle fibers."

The production of the sought-after meat analogs involves a complex piece of equipment called an extruder. It is the only equipment that can produce meat analogs with good, long fibers. In short, it can be described as a combined pressure cooker and meat grinder.

Karolina Östbring and Jeanette Purhagen have worked intensively with the equipment for five years. According to Östbring it is "incredibly complicated".

"My goodness, it is the most advanced equipment we have in our machine hall," she said. "This is because there is an immense number of parameters that can be set at an immense number of levels. It means that it is tricky but wonderful when it works."

Now the researchers have got the hang of the machine. A lot has been published already, and more studies are on the way.

They have also made a discovery that saves a lot of energy and thereby enables more climate-friendly products. Instead of the usual process of feeding the extruder with a dry powder, they introduce a protein solution through an input that is actually for clean water. This method skips an energy-intensive drying stage while the extruder uses less energy. Overall, energy consumption is reduced by about 75%.

"It was not possible to patent the discovery, as the whole patent system is based on adding a step, rather than removing and simplifying. So, we have now published the discovery instead," continued Purhagen.

This means that the Lund team is currently the only one producing meat analogs in this way.

Finding the optimal combination of vegetable proteins to feed into the machine is just as important as finding the right settings for the extruder.

The researchers have experimented with, among other things, rapeseed, hempseed, yellow peas, chickpeas, broad beans, oats and gluten (from wheat), often in the form of protein and fiber-rich residues from agriculture and the food industry, which further increase the environmental benefits.

"The research field has begun to realize that one raw material cannot do the whole job, rather you need to combine two or more raw materials to attain a really good mouthfeel," said Östbring. "Often you need a raw material that adds protein and one that contributes fiber, so that the product won't be too rubbery."

Taste is also a challenge, as many plant components cause a bitter taste that can be difficult to filter out. So which one was rated most highly? "Hempseed behaves in a really tremendous way," noted Östbring, before adding that industrial hemp is used, more specifically the press cake left over from hempseed oil production.

"This residue contains a lot of high-quality protein, it has fantastic texturing properties and tastes good," Östbring reported. "The plant can be grown in Sweden and what is left over can be used for textiles and building material."

Used with gluten, the hempseed acquired a rounded taste and a good chewy texture that was appreciated by the panel. This combination was selected as the favorite.

The next-best rated combination was hempseed and residues from oat milk production.

While the researchers themselves aren't commercializing the product, there is interest from several companies. This process could take between two and five years.

Their related research has been published in the journal Foods, Journal of Food Engineering and LWT.

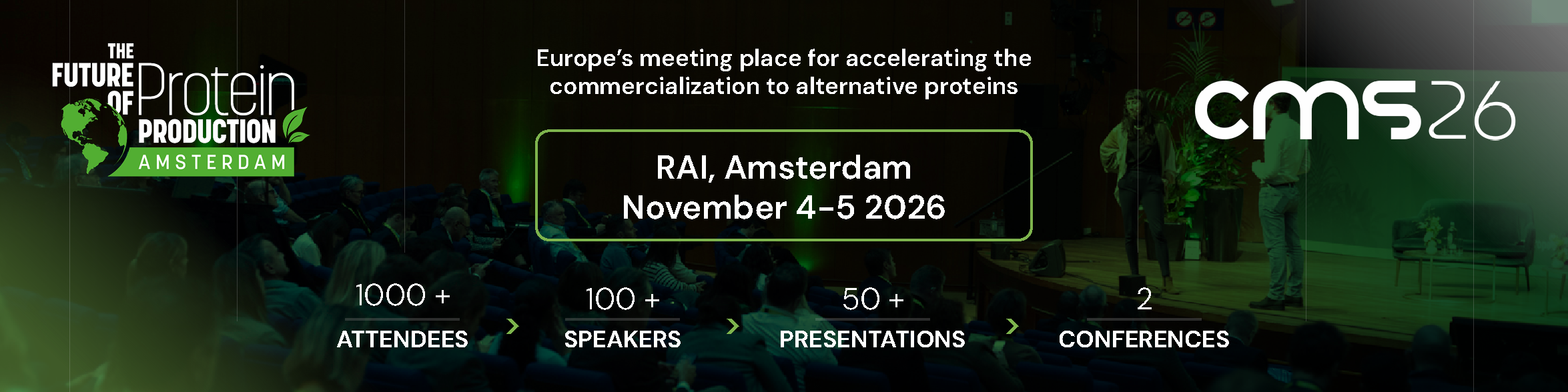

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)